Governments around the world are considering daring new research and innovation initiatives to meet the emerging challenges to our health and environment. With the announcement of two new DARPA-like agencies, the Biden administration is rising to the challenge. Europe has its own answer, but some crucial elements may be missing.

The recently released budget request for the 2022 fiscal year, though preliminary in nature, already indicates the extent to which the Biden administration is committed to the so-called “DARPA model”. In addition to an increased investment of $1 billion in the existing Advanced Research Project Agency – Energy (ARPA-E), the request proposes the creation of two new agencies: the Advanced Research Project Agency – Climate (ARPA-C) and the Advanced Research Project Agency – Health (ARPA-H). In an era of declining fossil fuel reserves, climate forcing by human activities, and a global health crisis related to the COVID-19 pandemic, the need for disruptive innovation in these sectors is already clear. Still, the choice of model used as a template is instructive.

The near-legendary Defence Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA), which opened the way for such technologies like GPS, stealth technology, the internet and lasers, has more than justified its existence since its founding by the Eisenhower administration in 1958. Its goal “to prevent and create strategic surprise”, taking ideas at the forefront of science and technology and rendering them possible, is exactly the attitude needed to meet challenges in an increasingly complex world. The COVID-19 pandemic is just the most recent of what are sure to be many future crises that highlight the need for nations to pool resources (both financial and brainpower) to address increasingly global problems. However, a DARPA-like approach, indispensable in anticipating and staying ahead of future crises, has so far eluded Europe.

Europe is a continent with a rich tradition in radical innovation in the humanities and the sciences, with both member-state and supranational funding mechanisms such as the European Research Council (ERC) contributing to its status as something of a “Nobel laureate factory”. However, the comparative dearth of disruptive technologies coming from Europe has repeatedly led to calls by such people as the former European Commissioner for Research & Innovation Carlos Moedas and current President Emmanuel Macron for a pan-European innovation organisation charged with emulating the success of DARPA.

Although the need to double up on efforts to create European centres of excellence in research and innovation has been recognised and acted upon, attempts at setting up a DARPA-like agency have been fruitless to date. No European country has the resources to go it alone, although some in France and Germany have floated the idea. For example, the Joint European Disruptive Initiative (JEDI), set up as a non-profit by André Loesekrug-Pietri in late 2019 with endorsement from the French President, has so far lacked the financial firepower to match its ambitious plans as it is backed solely by foundations, philanthropists and donors.

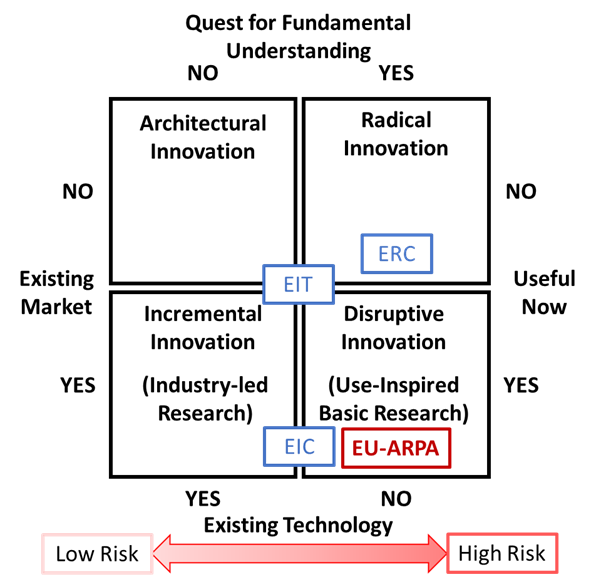

The creation of the European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT) in 2008 and the European Innovation Council (EIC), piloted under Horizon 2020 and expanded under Horizon Europe, represent the effort at a European level to bridge the gap between academic research output and translation of this output into disruptive commercial innovation. These are welcome developments in the European innovation ecosystem, especially when coupled with the European Green Deal, which contains such elements as the Just Transition Mechanism and the Farm to Fork strategy. Still, it could be argued that they miss some of the key ingredients needed to generate disruptive technologies on a par with DARPA.

As explained by William Bonvillian, an expert on the DARPA model based at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), the reasons for DARPA’s success are alluded to in its name. DARPA has always been a project-driven agency, operating at the forefront of understanding (Advanced Research) under a thematic area (Defence). Its programme managers evaluate progress at the end of each phase of a project and, should performance be judged to be unsatisfactory (in the sense of requiring too much of an investment in time to produce tangible results as set out in the project brief), they cancel it and redirect resources to better-performing projects. This dynamism is also reflected in DARPA’s relatively flat organisational structure, the autonomy granted to programme managers in selecting and running projects, and their short tenure as managers. Finally, prototypes developed by DARPA find a willing client in the US military, picking up a nascent technology and taking it to a point at which it can be commercialised.

Part of the justification for creating a European DARPA-like agency is the position it would occupy on a quadrant representation of innovation concerning markets and technology relative to the ERC, EIT and EIC. With a network of over 1000 partners spread out across the territory, the EIT seeks to drive “innovation across Europe by integrating business, education and research to find solutions to pressing global challenges.” As such, the EIT straddles the boundaries between pure basic research and industry-driven research. As an “impact-driven” tool with more emphasis on user base, the EIC fund can be situated between industry-led and use-inspired basic research. Working on projects that combine a quest for fundamental understanding with existing markets (i.e. that address existing challenges), a European Advanced Research Projects Agency (EU-ARPA) would focus its efforts purely on disruptive innovation.

For example, the EIC Pathfinder scheme, intended for researchers and technologists to take projects from a proof-of-concept to commercial viability, states: “if the path you want to take is incremental in nature or known, EIC Pathfinder will not support you”. Admirable as it is, this approach may bear more fruit if used to pick up and develop a path first rendered “possible” by one or more EU-ARPA projects. This arrangement, more in keeping with the principle of division of labour, would mimic the roles of the US army as implementor of technology, freeing DARPA to focus on its role as a technology development organisation. There is further the question of culture. Members of governmental and bureaucratic structures are understandably trained to avoid risk and failure at all costs. However, ARPA-like agencies pursue inherently high-risk projects and require a high tolerance for failure. It would thus make sense to de-lineate EU-ARPA from other projects.

In the proposed EU-ARPA, programme managers would have as much freedom as possible in the scope and direction of their projects. Some degree of governmental oversight would doubtless be necessary, but the responsibility for risk analysis would largely lie with programme managers that are experts in the field. In contrast, although the EIC has already undergone some structural changes to “simplify” the application procedure for its programmes in response to feedback from its pilot phase, the necessary rules around financial accountability (particularly relevant where commercial partners are involved) would likely limit the freedom of action in many of its projects.

The “high-risk” aspect of a DARPA-like agency relates to the financial commitment it takes to tolerate many project failures and dead-ends; the “high return” refers to the ability to shape the future technology landscape via the projects that succeed. As such, should Europe wish to emulate the success of DARPA, it must at least match its roughly $3billion annual budget. Financial muscle has already been earmarked under the Global Challenges pillar of Horizon Europe with a proposed budget of nearly EUR 53 billion over the next six years, so the opportunity is there. In contrast, the £800 million proposed for a British “ARPA” (working title) in its 2020 budget is unlikely to amount to much unless combined with funding from elsewhere.

Moreover, the thematic clusters of pillar II offer an opportunity to mandate the focus of research. DARPA (or ARPA at the time) was born in the aftermath of the launch of Sputnik and the Eisenhower administration’s fear of Soviet technological supremacy. Further examples such as that of Bell Labs show that a degree of mission focus (improving telecommunications technology in the case of Bell Labs) is beneficial but only insofar as the quest for fundamental understanding isn’t threatened.

A funding model similar to the European Space Agency, in which mandatory national member state (GNP-adjusted) contributions are supplemented by optional contributions, might be the way to go. However, funding operating along the principles of geographic return should be dealt with carefully; every constraint placed upon project managers would risk undermining an environment unencumbered by heavy bureaucratic oversight that was key to DARPA’s success. This could be achieved by devising a method to calculate member state return upon successful completion of a project rather than applying preconditions at its outset.

Whatever the funding mechanism, a European ARPA would need an unusual combination of attributes. It should position itself carefully in the innovation landscape to avoid fading into obscurity within the sea of existing acronyms in Europe. It would need a culture of daring ambition verging on the absurd, a thirst for knowledge, a tolerance for failure, generous patronage that keeps form-filling to a minimum, and a dynamic horizontal structure unified in the desire to meet a thematic challenge. A tall order perhaps, but we know that it can be done. Europe should dare to make it so.